Remembering John Powell Davies

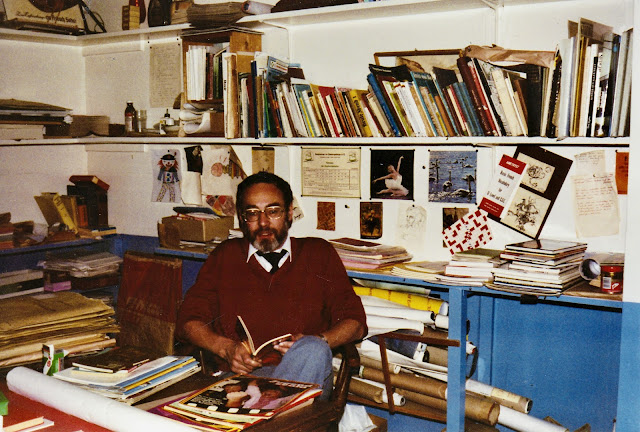

Special thanks also goes to Katy Oxton who was kind enough to send me a selection of photos she took at the school in the mid-1980s. They included the only known photo of Mr Powell Davies in the classroom (below). We will be publishing all of Katy's photos very shortly in an upcoming post.

Although I wasn’t taught by Mr Powell Davies (my maths sadly wasn’t good enough to get me into the top set) I remember him well and got to know him a little better later on when I was a volunteer with Colchester Samaritans. John would often come to social events with his wife, Rosemary, who was a long serving volunteer and director of the branch between 1979-1984. I remember John joking on more than one occasion about wanting to become a volunteer! I have very fond memories of Rosemary - she was such a kind and compassionate person and exactly who I would wish to be on the end of the phone for me if I was in need.

A further clue for us was his frequent advocacy of transcendental meditation. Few of us, as he knew, had ever heard of it and I do not know how many ever took up his offer of introduction to a local group. This was, of course, years before schools offered the sort of care now embodied in curricula and mindfulness. I recall a parents’ evening when instead of showing any interest in me he attended only to my father, immediately recognising a fellow soul scoured by the past.

And yet there was another unexpected side to John Powell Davies; his devotion to debate and public argument that expressed itself in membership of the local Rotary Club and a lively evening debating society that met regularly in the school library of the Gilberd. If memory serves, I fear (from current perspectives) that it was men only, but he took a teenage me under his wing, persuaded me to lead a debate in the library one evening (and fixed it so that I won), attend a Rotary charity lunch in Jacklins, then the centre of High Street news and social gatherings before it closed, alas, in 1997, and phoned up one evening with an invitation (that I didn’t have the confidence to accept) to join a debating team touring the US.

Looking back, one remembers John Powell Davies with even greater respect and admiration and what a privilege it was to have known him – and yet part of that was how, from your first meeting with him, even when young and inexperienced, he had immediately impressed with his commitment and depth of understanding.

17th October 2021

-----------

John Powell Davies - Obituary Thursday 16th December 2004 (The Times)

Naval pilot who was imprisoned in Colditz and returned from the war to become a gifted mathematics teacher

At the time that John Powell Davies was consigned to the famous German prisoner-of- war camp at Colditz Castle, he was the youngest inmate and, at the rank of midshipman, the most junior.

Colditz was the final camp for persistent escapers. Powell Davies used to aver with modesty that “it was much easier to get into Colditz when I arrived than afterwards”, but although unsuccessful, he did make attempts to escape from other camps, notably from hospital shortly after being captured and while incarcerated in a fort in Poland. There he noticed a sally-port tunnel filled with barbed wire which he and a friend laboriously snipped their way through, only to find an alerted bunch of guards at the other end.

His more than four years in Colditz were pretty depressing — he did his bit in supporting the “escape committee” in various minor ways but was too young and junior to feature as an escaper. He exchanged language lessons with French and Polish officers and became fluent in French, Polish and Russian.

After writing to his girlfriend, Rosemary Plowman, he wrote to anyone he knew asking for food parcels, striking it lucky with a neutral Portuguese friend who sent tins of sardines. His letters to a German family, the sons of which he had tutored before the war, received no replies. Powell Davies heard afterwards that, although the family hadnegotiated as high as Goering, they had been warned off a “Colditz bad boy”. On release he weighed 7st (44kg).

John Powell Davies, despite winning a scholarship to Cambridge to study engineering, was forced to leave school to get a job after the death of his father. A summer tutoring in Germany was followed by training as an actuary, which he heartily disliked. After failing his first-year exams, he answered an advertisement for naval pilots. Qualified for frontline service, yet not 18 years of age, he was appointed to the carrier Glorious whose two escorting destroyers were subsequently sunk under controversial circumstances with the loss of almost all hands.

He was wounded and shot down near Cap Gris Nez but managed to land in shallow water and wade ashore. This happened while “gardening”, the euphemism for minelaying off the French and Belgian coasts. He always considered this operation a waste of time until he learnt that the Germans would send out a standardised message after each attack which helped Bletchley Park codebreakers to solve that day’s signal traffic. He regarded his capture in some ways a second piece of luck as so many of 825 Squadron’s aircrew did not survive the war.

On return to England, he married Rosemary in his naval uniform, the only suit he had. He then took up his Cambridge scholarship, eight years late, to study engineering.

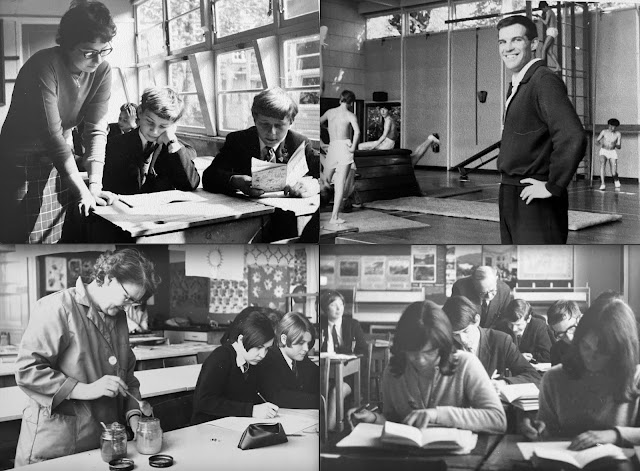

At the age of 35 he found his true metier as a gifted mathematics teacher, first at the Colchester Royal Grammar School and then at the Gilberd School in Colchester where he was head of the mathematics department. His pupils recall him as a teacher of great presence and one to be listened to with care and attention.

In later life he was an active member of the Colditz Society, often known as the Monopoly Club because Waddingtons, the makers of the game, sent escape materials to them hidden inside the boards.

His wife predeceased him; he is survived by three of their four sons.

John Powell Davies, naval aviator, Colditz prisoner and schoolteacher, was born on September 27, 1920. He died on October 3, 2004, aged 84.

Photos

I'm extremely grateful to Mark Powell Davies for providing a large number of images of John taken during the war. Not a lot is known about some of the photos but each image is captioned as fully as possible.

My first-year form master and maths teacher at Colchester Royal Grammar School in 1968. A gentle giant of a man.

ReplyDelete